1) What are the main challenges facing press freedom, particularly since the shutdown of independent media outlets starting in 2017 and the ongoing crackdown on social media?

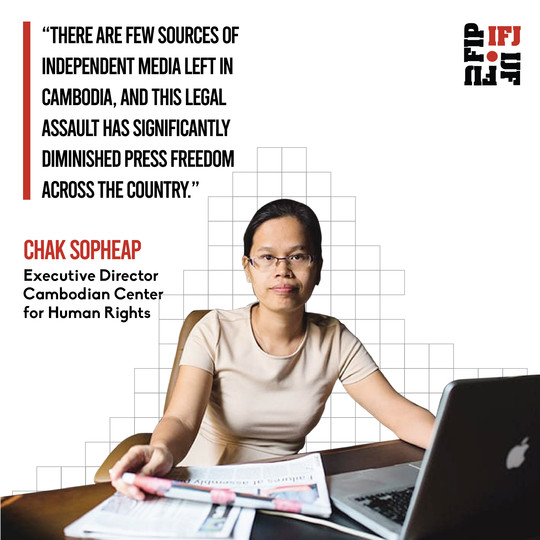

Freedom of expression and freedom of information are fundamental human rights which are guaranteed under Cambodian and international law, and press freedom is a crucial component of these rights, as well as being vital to a healthy democracy. However, journalists and the media in Cambodia continue to face significant judicial harassment and intimidation in violation of these rights. This has taken the form of arbitrary arrests of journalists and the widespread shutdown of independent media outlets using a range of legislative tools, such as tax regulations or the Lese Majeste criminal offense. There are few sources of independent media left in Cambodia, and this legal assault has significantly diminished press freedom across the country. This is continuing and has been exemplified recently with the arbitrary arrest of TVFB reporter Sovann Rithy for sharing a quote from Prime Minister Hun Sen on social media and the subsequent swift license revocation of TVFB. This continued harassment encourages self-censorship amongst Cambodian media outlets, who cannot report freely and independently or criticize the actions of the Royal Government of Cambodia (“RGC”) for fear of similar treatment. It is the responsibility of states to ensure the media are not restricted or intimidated. Unless this harassment and intimidation of journalists and media outlets stops, and freedom of expression and information are respected, press freedom cannot be a reality in Cambodia.

2) Recently new emergency laws in Cambodia have been passed under the Covid-19 pretext, granting Cambodia’s leadership vast new powers. How will these laws affect press freedom?

The draft ‘Law on the Management of the Nation in State of Emergency’ is extremely concerning as it grants the RGC extensive and unfettered powers to restrict human rights without sufficient checks and balances. There is potential for this law to severely curtail press freedom in Cambodia as it includes powers to further surveil all telecommunications and restrict the sharing of information through news and media. For example, Article 5(11) of the draft law allows the RGC to ban or restrict news sharing or media which is able to “cause panic or chaos or bring damage to the national security or make confusion about the situation of the state of emergency”. This provision is extremely vague. Considering the long-standing suppression on free and independent media in Cambodia by the RGC, and the recent worsening of this during the Covid-19 crisis, such as the arbitrary arrest of TVFB reporter Sovann Rithy and the increase in arrests for sharing ‘fake news’, this is an alarming amount of power given to the RGC to further quash press freedom. The RGC has reported to the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights that they will only use the law in compliance with their obligations under international human rights law, upholding the principles of accountability, proportionality and necessity, however this assurance alone is insufficient. The observance of these principles should be written into the law itself to prevent abuse, misinterpretation and misapplication. The RGC must revise the law to include limitations on the exercise of these powers, and only implement this law appropriately in genuine states of emergency with respect for human rights, including press freedom.

3) We have seen an increase in cooperation between China and Cambodia with the launch of the Cambodia-China Journalist Association (CCJA) and a program which encourages media to write positive news about collaboration between China and Cambodia. Can you elaborate on the impact of the influence of China on the press freedom in Cambodia?

China is Cambodia’s largest creditor and source of foreign direct investment, and ties with China are growing stronger. This must not be permitted to interfere with the free and independent media in Cambodia. Free and pluralistic media is crucial to a functioning democracy as it ensures good governance and accountability. The RGC should encourage media pluralism and ensure the rights of critical and dissenting media outlets are afforded the same rights and protections as pro-government sources.

4) Vital amendments to the Press Law have been a long time coming. What’s the current status of these amendments?

Last year the RGC announced it would undertake consultation on and amend the Press Law (1995). Reportedly the amendments were to be regarding confidential information and intended to bring articles “in line with the current situation”. However, there have been no further updates on the status of the amendments, nor have any drafts been released. As free media in Cambodia has undergone systemic attacks and is subsequently severely depleted, any potential amendments to the Press Law must provide greater protection for journalists and the free media. The pending amendments must be in line with international human rights law, particularly freedom of expression, and must uphold Cambodia’s national and international human rights obligations.