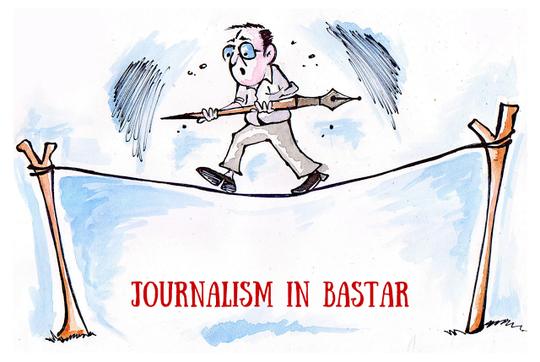

Defending the Messenger

Journalists in the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh have been under siege for the past several decades while living and reporting on the conflict between the banned Communist Party of India (Maoist) and the Government of India, with the vast majority of adivasi (indigenous people) villagers bearing the brunt. Journalists and human rights activists have been under threat for uncovering violations by the security forces and state-sponsored vigilante groups. With army operations having intensified in Bastar, journalists have been more at risk of harassment, false cases and intimidation, as noted by the IFJ in recent releases and its 2015-2016 South Asia Press Freedom Report.Journalists of Chhattisgarh organised under the banner of the Patrakar Suraksha Kanoon Sanyukt Sangharsh Samiti (United Struggle Body for the Security of Journalists), have demanded that journalists arrested under false cases be immediately released, and that the state create conditions for reporters to work and travel freely, without fear or harassment. As part of this initiative, journalists have also demanding that the state implement an Act that protects journalists from physical violence and arbitrary arrests. In response to this, the Chhattisgarh unit of the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) has proposed the draft The Chhattisgarh Special Act for Protection of Journalists and Human Rights Defenders, the first law of its kind.As part of the campaign to End Impunity, Laxmi Murthy interviews lawyers Sudha Bharadwaj and Shalini Gera who were instrumental in drafting the Act.

What are the unique features of the proposed Act?

The proposed Act seeks to offer some security to journalists as well as other human rights defenders (HRDs) in the practice of their profession. By the very formulation of this Act, there is recognition of the fact that the very practice of their profession makes journalists and HRDs vulnerable to assaults on their life, liberty and property, and secondly, that the work done by journalists and other HRDs is very valuable for the well-being of a society and hence, it is the state's responsibility to ensure that they can continue to do their work without fear and undue pressure.

This Act seeks to institute an autonomous body with quasi-judicial powers, the Commission for the Protection of Journalists and Human Rights Defenders. The Governing Board of this Commission will be constituted of representatives from the journalists, civil society group, retired judges of the High Court and representatives of the government, and will have powers to direct the State Government to take appropriate actions to safeguard the human rights of those who are at risk as a result of the exercise of their freedom of expression, and the professional pursuit of journalism.

The Act mandates that the Commission will seek to secure the human rights of journalists and journalist collaborators (such as stringers, camerapersons etc.), other human rights defenders, their next of kin and persons within their organization, group or social movement. The Commission will have a complaint mechanism by which either the journalist/ HRD himself or herself, or a third party on his/her behalf, will be able to lodge a complaint with the Commission. The Commission will also be empowered to take suo moto action, if a violation is brought to its notice. The Commission will then make an assessment about whether or not the complaint describes an emergency requiring extraordinary measures, and if it does, then the Commission will implement an Urgent Protection Measure within 12 hours of receiving the complaint. Routine protection measures will be implemented within a week, and the Commission will also have its own Special Investigation Unit that can carry out independent investigations of complaints. The Commission is also empowered to grant damages and monetary compensation in the event of any assault on the life, liberty or property of a journalist, journalist collaborator or an HRD.

The Act also mandates that any impending arrest of a journalist, journalist collaborator or an HRD in any criminal matter would require the approval of this Commission. One of the tasks of this Commission will also be to maintain an updated database of all journalists as well as all media entities in Chhattisgarh. A journalist or journalist collaborator facing harassment, exploitation, pressure of unethical and unprofessional nature, threat or victimization from the media entity with which he/ she is associated, may complain to the Commission, which will make efforts to arrive at a fair and just settlement of the grievance. In the event of no such settlement being arrived at, the case shall be adjudicated by the Commission in its capacity as a quasi-judicial body.

This Commission is distinguished from other Commissions we have experienced thus (such as the State Human Rights Commission, State Commission for Women etc.), in that the recommendations of this Commission are binding on the State Government. Also, the Act itself mandates a strict time limit with which the complaints to the Commission have to be dealt with, and also a minimum frequency for the meetings of the members of the Governing Board.

Besides setting up the Commission, the Act also institutes special Courts at district level to ensure a speedy trial in the case of an assault against a journalist or HRD, or a case where the journalist or HRD are facing criminal charges. The proposed Act also protects journalists’ sources and makes the procurement of information by a journalist from the source an act of "privileged communication" where the journalist cannot be compelled to disclose the identity of the source.

Why it was thought necessary to have a separate law? What are the lacunae in existing laws that promote impunity for those who commit crimes against journalists?

The current laws do not recognize the special risk being faced by the journalists as they try to provide unbiased and independent news, especially in a conflict zone such as Bastar in Chhattisgarh. Consequently, there have been a large number of journalists killed and assaulted in their line of work, imprisoned or otherwise intimidated by the agents of state as well as private players.

In 2015, a sub-committee of the Press Council of India (PCI) – a quasi-judicial authority – has prepared a detailed report on the attacks faced by working journalists, after visiting 11 states. The report states that 80 journalists were killed in India since 1990 and in most instances, except the Shakti Mill gang rape case, all other cases are still pending in the courts and in some the police are yet to file charge-sheets. With four journalists dying in the line of duty in the duration of just over a month, the Press Council of India (PCI) had demanded in this report that a separate law be enacted for the safety of journalists across the country. The PCI report was submitted to the Union Minister for Information and Broadcasting, Arun Jaitley, during the 2015 monsoon session of the Parliament.

Chhattisgarh has also seen a fair amount of violence against journalists, especially those working in the conflict zones of South Bastar. On February 12, 2013, Chhattisgarh-based freelancer Nemi Chand Jain’s body was found the morning after he had left his home for Nama village in Sukma district of Chhattisgarh suspected to have been killed by Maoists. On April 11, 2012, local political activists attacked the District Bureau Chief of the Hindi daily Rajasthan Patrika, Kamal Shukla, at his office with iron rod in Kanker, Chhattisgarh. On December 20, 2010, some assailants shot dead Sushil Pathak, a journalist with Dainik Bhaskar, at close range while he was returning home in Bilaspur Chhattisgarh, after a late night shift. In January 2011, Umesh Rajput a reporter with the Nai Dunia newspaper was shot dead at his home in Chhura village in Gariyaband district. Several journalists have been facing malicious prosecution and defamation cases because they reported on misdeeds of corporate or powerful bureaucrats. Certain newspapers who reported against powerful vested interests also faced state-sponsored physical violence.

In the past year, four journalists in the Bastar Division have been incarcerated. Santosh Yadav, was arrested by police on September 29, 2015 and Somaru Nag, an Adivasi journalist, was arrested on July 16, 2015, from the Darbha block of Bastar, on charges of supporting Maoists whereas they were known for reporting against police excesses. On March 21, 2016 journalist Prabhat Singh was picked up by the police and charged with offences under the Information Technology Act for a WhatsApp message making fun of a senior police officer. Later, he was also booked under other offences. Soon after, on March 26, 2016, journalist Deepak Jaiswal was also arrested as a co-accused of Prabhat Singh in a seven-month old case, accusing the duo of assaulting and obstructing public servants in a school, while they were reporting against institutionalized cheating. These arrests have been widely condemned as being politically motivated and as retaliation for the reporting by arrested journalists.

It is in recognition of this special risk that was being faced by journalists that this special Act for their protection is being proposed. It is of utmost interest to the functioning of a vibrant democracy that its journalists are able to work in an atmosphere of security and feel empowered to fearlessly report on any issue.

Can this law serve as a model for a Central law?

Yes, it can definitely serve as a model for a Central Law. Suggestions from other parts of India on the specific threats facing journalists there can be incorporated in this to be make it a more robust Act.